| Organisational Inquiry: General and Simple to Simple and Accurate |

Leaders Acknowledging Trade-Offs

Curious leaders want to know what’s going on in their organisations, the issues that might be impeding high performance and what their colleagues are really thinking. Curious and determined leaders make it their business to find out the answers to these questions, but do they understand or acknowledge the inevitable trade-offs of conducting inquiry and determining both causality and solutions?

The most important trade-off in determining how an organisation functions is the difficulty of reconciling the relationship between behaviour that is categorised as general, accurate and simple, i.e. it is impossible for the purpose of analysis and provision of solutions to, simultaneously, encompass all three dimensions. The more general a simple explanation is, for example, the less accurate it will be in predicting specifics.

The GAS Model

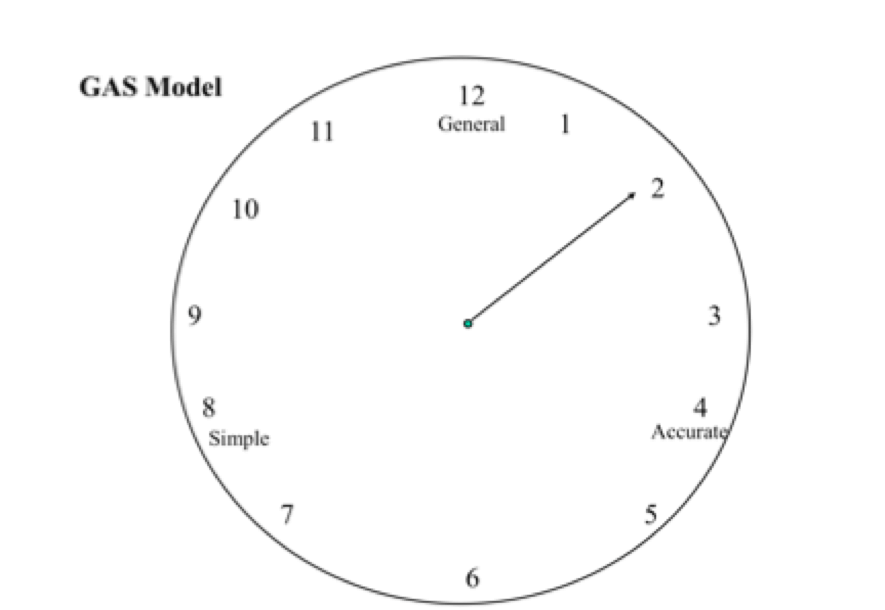

To understand the implications of the trade-off between general/simple/accurate (as outlined by Weick in 1999)1 it can best be conceived as the face of a clock. At the twelve o’clock is the word general, at the four o’clock is the word accurate, and at the eight o’clock is the word simple.

1 Karl E. Weick (1999) “Conclusion: Theory Construction as Disciplined Reflexivity: Tradeoffs in the 90s” The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Oct., 1999), pp. 797-806Karl E. Weick (1999) “Conclusion: Theory Construction as Disciplined Reflexivity: Tradeoffs in the 90s” The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Oct., 1999), pp. 797-806it

Philosophy of Model Page 2 of 5 Footdown Ltd Copyright 2015 July 2015

The working mnemonic device to store away these observations is simply the word GAS. If we display the trade-off across the clock face, we can see the dilemma inherent in any diagnostic or intervention strategy. If you try to secure any two of the virtues of generality, accuracy, and simplicity, you automatically sacrifice the third one.

For example, general/accurate must apply to a defined population and be universally applicable within that population so it is very difficult to apply because as the population is expanded the ‘one size fits all’ (generality) motif is lost. Accurate/simple is accurate, but its generality is suspect – so here we could conceive of a case study and summarise events in one organisational setting in a manner that conveys a simply formed accurate narrative, but here it is only applicable to a restricted population because we have lost its generalised applicability. Finally, the general/simple combination conceives analysis and/or solutions that are easily expressed and generally applicable but at the level of principle rather than detail because we have sacrificed, or traded-off precision in order to take in wider meaning and applicability.

Traditional responses to the Trade-Offs of Organisational Interventions

Organisational researchers and management consultants alike, appreciate the dilemma that the GAS model creates for both inquiry and consultant based inquiry. This explains the researcher’s preference for longitudinal study aimed at theory that is difficult to form, narrowly focused, and late in coming to the notice of practitioners (it has to be scrutinised by peer review and eventual publication in scientific journals; this can take several years from the point when data is collected, and even then the ‘readability’ and applicability of the work is, often, questionable).

The Management Consultant, however, will create a series of general/simple templates (that can be traced from the general/accurate work of researchers) and present them to potential clients as a ‘shop window’ that provides a panacea for analysing and correcting organisational issues. These are treated with universal scepticism by professional researchers who recognise that, at best, these will be broad-based generalisations or conversation pieces that, on their own, mislead and fail to add value to organisations.

Despite the treaties for professional researchers to generate relevance for practitioners through knowledge transfer it causes stress because it takes them into the case specific analysis and solution provision of the simple/accurate positioning on the GAS model and this is not what they are trained to do and neither is it what they are rewarded (professionally) for doing.

For the management consultant the problem is reversed; they want to dwell in the client specific area of simple/accurate because this is where the bulk of their fees are likely to be earned but without the time and complexity of dwelling, for too long, in the theory generation of general/accurate. This is not what they are trained to do and neither is it what they are rewarded (professionally) for doing……a familiar tale then!

Where does this leave the client?

The options for organisations that want robust and accurate analysis/intervention is to determine their own trade-offs. The professional researcher will provide general, but narrow, assessments through research and try and fit this into simple/accurate findings so that they produce actionable interventions (forcing complex theory into simple actions).

The alternative, management consultant-led, approach will be to either survey or interview large swathes of the organisation through their existing templates and then try to interpret these in ways that make sense through actionable interventions (basing accurate assumptions on generalised theory).

Both options described above will carry significant cost, time and disruption so all but large organisations will either do what they have always done, what their associates have done, whatever is the current management fad or more likely still, do nothing because it is too problematic and the return on investment is too uncertain.

Reconciling the tensions of the GAS Model

We suggest that rather than make square pegs fit round holes, diagnostic and intervention techniques designed at enhancing organisational capability should work with the, inherent, trade-offs of the GAS model, rather than fight against them.

As far back as 1947, a famous scholar, Kurt Lewin, coined the expression ‘there is nothing so practical as good theory’, e.g. try driving a car without understanding the theory of acceleration and braking! The novice driver does not need to understand the formula for the acceleration and deceleration of mass (general/accurate), but they do need to understand a general/simple theory (the faster you travel the longer it takes to stop) and be able to able apply it in a specific situation (driving a car) simple/accurate.

Lewin’s aphorism works at the macro and micro levels of organising, it guides us to conclude that for those wishing to design coherent systems of intervention rather than try and treat the three areas of the GAS model as, exclusively, separate parts of the problem, that they should be regarded as integrated (and equally necessary) aspects of the solution. The basis of any system of intervention should be grafted upon a strong theoretical model (general/accurate), that environments should be broadly scanned for anomalies, disturbance or patterns (general/simple) and that this should be used to conduct subject area detailed investigation (simple/accurate) from which practical inference and interventions can be concluded. In short, a system capable of taking complex actions and deconstructing them into manageable information from which simple (not simplistic) conclusions can be formed. Put another way a system that thinks complex so that people can do simple.